Polish Settlers at Dunedin

Dunedin was first settled by Scottish settlers in 1848, and by the 1870’s was a compact city as a result of the 1860’s Gold Rush. Most of its industry was situated on the original sliver of flat land and on the additional land reclaimed by dumping inconvenient hills and spurs onto the mudflats during the 1860’s. The factories were fuelled by coal, mainly shipped from Australia until the 1880’s when the West Coast Coalfields began producing large quantities.

By 1874, the waterfront was a straight line along the eastern side of Crawford Street. Water and Gas mains by this stage had been well established since the 1860’s. Telegraph wires ran everywhere in and around Otago, and before long railways would be almost as common.

The residential areas clung to the short, steep hills in the dress circle above the centre of commerce and industry. Larger, grander homes were further back, their owners able to afford a short hansom cab ride up the hill in preference to a short hard walk.

Anthony Trollope, novelist, who visited Dunedin in 1873, wrote,

“Dunedin is a remarkably handsome town – and, when its age is considered, a town which may be said to be remarkable in everyway. The main street has no look of newness about it. The houses are well built, and the public buildings, banks, and churches are large, commodious, and ornamental. The schools, hospitals, reading rooms and university were all there, and all in useful operation.”

But there were other features which Trollope on his brief visit probably did not see, or, in his surprise that there was anything of distinction at all in a new community at the ends of the earth, passed over. Ramshackle wooden relics of the gold days and earlier lingered on, shivering into decay. In certain streets and down repulsive alleys were areas of wretched slums. And above all there was the stink and filth of an undrained city. There were stagnant pools, un-reclaimed swamps, and unmade footpaths, in populous neighbourhoods of Dunedin. At the end of 1874 in terms of the Public Health Act of 1872, a medical officer would report monthly of the sanitary conditions of the city.

And so the central city became renowned for filth, stench and epidemics. Land prices soared. People began moving into the cheap land around the marshes of The Flat (South Dunedin), and some began settling on the drier areas, such as Kensington. Real estate agents described The Flats as ‘a salubrious meadow’ where health and vigour would be restored to those suffering from the fetid air of the city. Ozone became a metaphor for health, and The Flat had plenty.

The early eighteen seventies were boom years for New Zealand as a whole with the stimulus of the Vogel Public Works and immigration policy. Between 1872 and 1875 almost 18,000 people arrived in Otago, a larger number than was received by any other province. The old immigration barracks situated in Princes Street (built since 1860) were constantly occupied until the new immigration barracks at Caversham were established in 1873.

The former north wing of the Caversham Immigration Barracks, now at 2 Elbe Street, Mornington in Dunedin, taken in 2022, courtesy of Paul Klemick

The two-storied wooden buildings were situated at the foot of Caversham Valley where the bowling green lies today. The barracks housed single men and women in the north and south wings, and married couples in the western wing. In 1888, after assisted immigration ended, the married couples cottages had largely been sold or destroyed. For some years the barracks was used as a fever hospital and when finally demolished the timber was used for local housing in the South Dunedin area around 1905.

The Census of 1874 recorded a population of 18,499 in Dunedin an increase of 3,642 since 1871, not including outer Dunedin. On this basis Dunedin retained its position as the largest city in New Zealand and the centre of the country’s manufacturing.

While the death rate had decreased since 1865, it was still far too high. According to figures it stood at 22.7 per thousand for 11 months of 1874, representing 24.8 for the complete year, and this in a city where there as yet were very few old people.

The chief products of Otago were gold and wool, but agricultural pursuits were extending themselves in all parts of the province. The farmers were in debt to the bank however, and their lands not infrequently sold under mortgage. Prices for farm produce were poor, as in some cases not even meeting the cost of labour, which took to produce it. But such complaints were general all over the world at that time.

The Otago Province in 1873 being only, twenty four years old, had 70,000 inhabitants, and above four million sheep.

When compared to Western Australia at the time, Otago had good climate, good soil, and mineral wealth. They had little or no convicts, nor had the land been wasted by great grants as was the case in Australia.

In the last quarter of 1871, the Government entered into an agreement with Messrs John Brogden and Sons of England to build the remainder of the Dunedin – Clutha line, a portion of track across the Taieri, to be completed by the 1st of September 1875. They hoped to meet this demand by bringing immigrants from abroad under contract to work for them at wages not less than 5 shillings per day, the firm to retain one-fifth of the wages until the passages were paid. The official opening of the new works took place on Saturday the 18th of March 1871. The site chosen was a paddock belonging to Mr. E. B. Cargill, at Kensington, Dunedin, where shortly before 2 o’clock between 200 and 300 people gathered.

The railway line from Dunedin to Port Chalmers was opened on the last day of 1872, and the southern line, as far as Abbotsford on 1 July 1874. The first Dunedin Railway Station stood on the ground, which now bears the Queen Victoria Statue. The line was laid outside the edge of Crawford Street and the south line crossed what is now King Edward Street.

In December of 1872 saw the arrival of first Polish immigrants to the city, from the ship Palmerston. Here they spent their first Christmas Eve in the Immigration Barracks situated near the corner of Princes and Police Street.

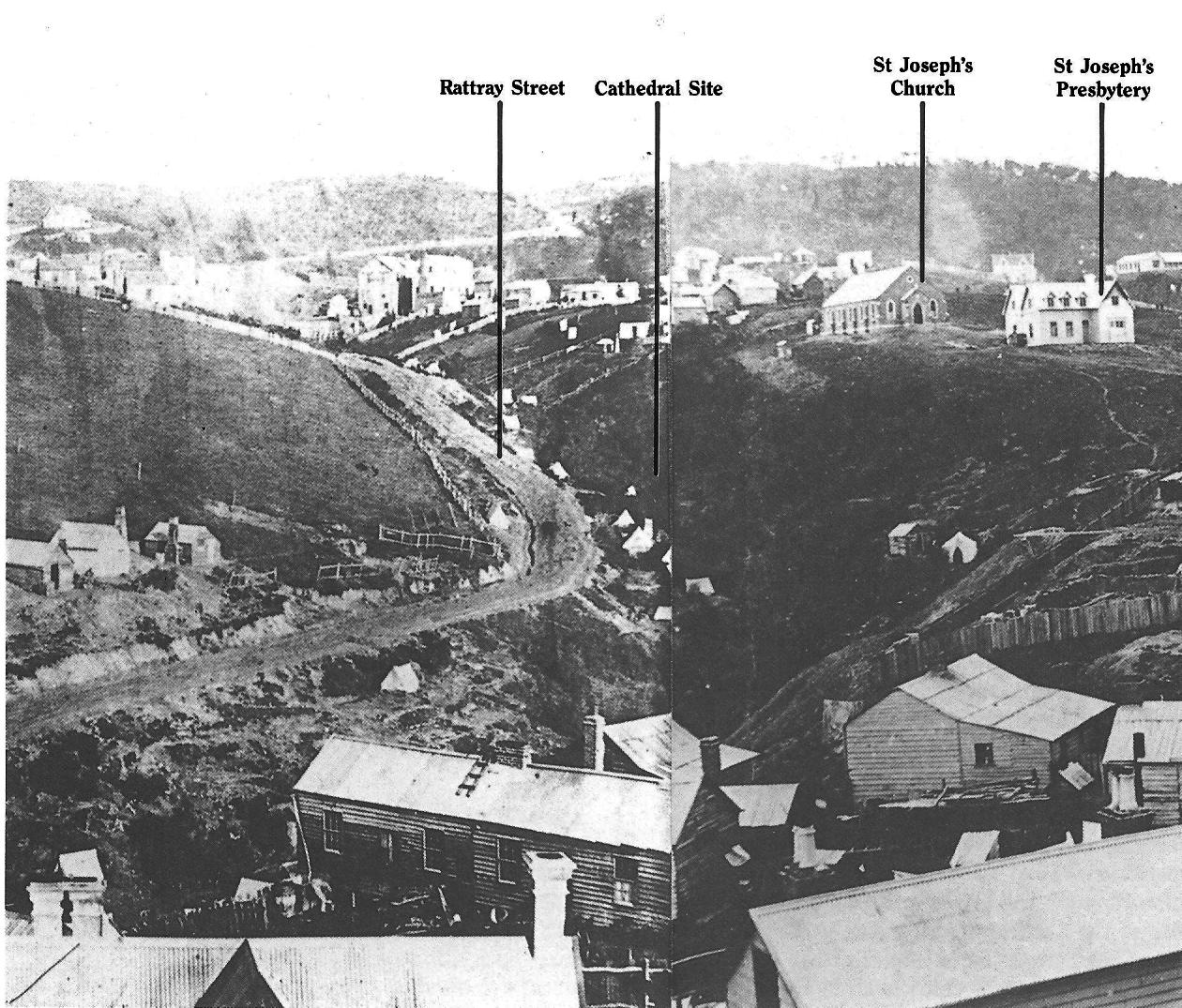

On Christmas day, the Polish settlers celebrated their first mass in the new country at the chapel of St. Joseph’s, where the baptisms of Mary Buchols, Mary Kowalewski and Martha Mehalski took place. The brick church was opened on 20 July 1862 by Fr. Moreau SM, the first Catholic priest based in Dunedin in 1861. The Diocese of Dunedin was then created on 26 November 1869, and the first Bishop, the Right Revd Patrick Moran, DD arrived on 18 February 1871. He found the church could only contain one-sixth of the Catholic Congregation of Dunedin and was destitute of the necessaries of Divine Worship, such as altars, vestments, chalice and suitable altar ornaments. In 1876, the church was enlarged, with a new organ gallery. However it would take another fifteen years before a larger Cathedral would meet the needs of the diocese. The organ was dismantled and re-erected just in time for the opening of the new St. Joseph’s Cathedral on 15 February 1886, which was designed by architect, F. W. Petre and cost £20,000 to build. The old church was later used as a school and hall before being demolished in the 1990s.

Early Polish Marriages held in St. Joseph’s Cathedral;

1886, 15 Sep, Adolpf Secher – Rosalie Konkel

1892, 26 Nov, William Cromar – Anna Teresa Kreft

1896, 22 Jan, John Trapski – Delia McGrath

1897, 29 Sep, Michael John Konkel – Margaret Thompson Barrowman

1901, 13 Feb, Frank Smolenski – Margaret Brennan

1904, 13 Jan, Francis Perniskie – Bedilia Tobin nee O’Gorman

1905, 10 Aug, Richard William Anderton – Mary Harrington nee Orlowski

Funerals at St. Joseph’s Catherdral.

“DEATHS. BISCHISKIE.—On January 5, 1919, at his residence, 74 Grange street, Julius, beloved husband of Mary Bischiskie, and father of Albert Bischiskie, of Christchurch; aged 79 years R-I.P- —Requiem Mass at St. Joseph’s Cathedral To-morrow (Tuesday), the 7th inst., at 7 a.m. Private interment.—Hugh Gourley, undertaker.” Evening Star, 6 January 1919, p 4

“DEATHS. KONKEL.—On December 17, 1925, at her residence, Pine Hill, Bridget, relict of Phillip Jacob Konkel; aged 92 years. R.l.P.—Requiem Mass To-day (Friday), the 18th inst., at 9 a.m., at St. Joseph’s Cathedral.” Otago Daily Times, 18 December 1925, p 8

“DEATHS. SWITALLA.—On May 18, 1933, at Dunedin Hospital, John, dearly beloved husband of Martha Switalla, of Allanton; aged 75 years. R.l.P.—Requiem Mass at St. Joseph’s Cathedral To-morrow (Saturday), May 20, at 9 a.m.—The Funeral will leave the Cathedral on Saturday at 10 a.m. for the Anderson’s Bay Cemetery.—W. H. Cole, undertaker.” Evening Star, 19 May 1933, p 6

Looking up Rattray Street, Ca 1863, courtesy of Catholic Archives, Dunedin

Most of these Poles were transported south to the township near Scroggs Creek (Allanton) to set up camp before being allocated to work on the railways while some remained in the city looking for general work or farm labouring. One such Pole was Julius Byszewski who found employment as a cooper at Speights Brewery. During the night of the 22nd of February 1882 there was a tragic fire in their two-storey home in Smith St. The fire claimed the lives of the three eldest and also that of their twelve-year-old nephew who had stayed overnight because of bad weather. Albert Joseph was the only child to survive although injured when his mother fell on top of him from the upstairs window. His father tried to catch her as she could stand the heat of the flames no longer. She sustained very bad injuries and was admitted to hospital with Albert.

Looking towards the two storey wooden homes on the top left of View Street. Here the Byszewki family home was destroyed by fire in 1882. Photo Ca. 1880 http://hockensnapshop.ac.nz/nodes/view/5620#idx5620

“FATAL FIRE IN DUNEDIN. FOUR CHILDREN BURNT. DISCOVERY OF THREE OF THE BODIES.

A terrible fire broke out in a small wooden house in Smith-street, near the corner of Dowling-street, shortly after four o’clock yesterday morning, by which four children were burnt to death. The house was occupied by Julius Bischefski, his wife, and four children, who all slept upstairs.

The fire appears to have broken out on the ground floor of the building, and the family were not aroused till it broke through the upper floor. Bischefski and his wife got through a window, leaving the children in bed, but it was not known for some time that there was anyone in the house, as little attention was paid to the maddening screams of Mrs. Bischefski. When the Brigade arrived, however, the house was entirely enveloped in flames, and it would have been too late to have rendered any assistance. The names of the four children who were burnt were-

Francis Bischefski, aged 8 years,

Minnie Bischefski, aged 6 years,

Martha Bischefski, aged 4 years, and

Thomas Croft, aged 13 years.

The fire spread to the next house on either side, both of which were destroyed.” Otago Daily Times

Some Poles who remained in the city worked as contracted farm labourers or purchased small holdings for themselves. A small number braved the often hostile conditions in the isolated settlement at Pine Hill which was close to the Mount Cargill Lookout.

PINE HILL

Pine Hill was not officially named as such but a descriptive name that gradually came into official use in Harnett’s Directory of 1866. Just as the forest had become grazing land, houses gradually intruded on the pastures. Residential Pine Hill was established around 1870 and had become well established by the turn of the century. But it was not officially recognised as part of Dunedin until 1910.

The heaviest settled area was from the foot of Cowan, then called District and later Waterloo Road, upwards to the summit of Mt. Cargill, where homes and farms were carved out of heavily forested, ten, twenty and fifty-acre-blocks. Pine Hill road was steep and rough, winding narrow and sinuously up from Great King Street bridge, requiring careful negotiation of cattle ruts. Given the “torturous” incline up to the Pine Hill district, the community in the 1870’s was probably quite isolated from the Dunedin Township.

Remains of Philip Jacob Konkels corrugated iron cottage at the entrance of block 32 on Cowan Road, owned by Gdanitz, Pernisky and Konkel, taken 2015, courtesy of Paul Klemick

The Polish families and individuals who first settled at Pine Hill in 1873, via the Palmerston, were; Jacob Gdanitz, Maria Gdanitz (via Cumberland Street), Joseph Kreft, and Johanna Plew who married Herman Henrickson and lived for a short time in the district before moving to the the North Island. Thomas Gdanitz and his wife, arrived in the district later in 1874, via the Reichstag. In 1883 saw the arrival of the families of Philip Konkel, via the Palmerston, and Antoni Pernisky, via the Dallam Tower, both families coming from the settlement of Allanton. The Polish setters who lived at various times on section 32 and 34, on the now Cowan road were firstly, Jacob Gdanitz, via a crown grant, who sold it to Antoni Pernisky in the early 1880s. Antoni later sold it to his son Frank Pernisky who sold it to Michael Konkel around 1911. Thomas Gdanitz worked as a dairy farmer in partnership with Joseph Kreft, until Thomas moved to Hampden around 1882. Jacob Gdanitz moved to Allanton around 1883. Antoni Pernisky, a dairy farmer purchased property at Allanton in 1886. Joseph Kreft left Pine Hill and moved his family to Allanton around 1888. Maria Gdanitz eventually moved to Frederick Street in Dunedin. Most of the original settlers in the district supported themselves by dairy farming, growing small fruits or timber milling. The saw milling industry employed many people of continental origin and supplied much of the timber for building early Dunedin.

“THE VALLEY OF THE LEITH (Mr Short’s Recollections)…The land on both sides appears to be almost all occupied. The settlers, a number of whom are German, have hitherto made their living chiefly from firewood, a tedious and toilsome occupation, and certainly yielding by no means an adequate recompense for the labour expended in procuring it. The appliances in use for this purpose are very varied — some of them rude enough, but apparently effective. A change, too, has come over the trade, necessitating additional labour. The timber has nowadays to be cut in short lengths, split up, and dried before it can be sold, and in this work both women and children are occupied. There are in some places a lot of fine red-pine trees still standing, but their time will ,not be long, a saw-mill driven by a portable steam-engine being busily engaged in producing from them building material.

With the exhaustion of this industry the settlers have been compelled to strike out a new course, and this apparently has taken the form of fruit-growing. Patches of strawberries are looking very healthy and promising, but the orchards have suffered severely from the hail showers and unfavourable weather of the month. The steep and broken character of the land renders it totally unfit for agricultural purposes, but it will prove well adapted for fruit culture, and in a few years the jam factories will receive from this locality a goodly portion of their supplies of the raw material.

Nor is it in the vegetable kingdom alone that this district has a good future before it. My companion, who is well posted up in geology, pointed out to me various mineral deposits which will yet come to be worked advantageously. Among these was hematite, from which paint is produced. At various points the red rock could be seen cropping out, which he considered equal in value to the celebrated ore of Nelson; and he said other colours also existed. Again he pointed out large areas containing lignite, which by means of cheaply constructed tramways could be easily brought to market. Shale, too,” from which oil is extracted, has also been discovered in the district.

We had now reached the Saddle at an elevation of 1000 feet. In amusing and instructive intercourse time had passed pleasantly. Of scenes of former days Mr Short has a large catalogue, and one describing his first purchase of a cow will bear relating. Like the rest of the settlers, he saw that a sure way to succeed was to become possessed of a herd of cows…” Otago Witness, 5 January 1884, p 10

A spectacular view of Dunedin city from Konkel’s property in upper Pine Hill, courtesy of Paul Klemick

The Pine Hill School was of paramount importance in the whole life of the closely-knit community. Dances, concerts, church services and polling were all held in its’ buildings. Even the mail was delivered to the school. A start on the original school building was made after the Otago Education Board bought a large tract of land (Section 16, Block X, North Harbour and Blueskin District) from the Otago Hospital Board. The intention was to build a hospital at Pine Hill but it was later decided that Wakari was more suitable. The Hospital Board would not sell in portions so the Education Board then subdivided the land and sold sections to those wishing to settle in the district. The first room of the school building and teachers’ residence was constructed using materials obtained from the Pine Hill bush. The logs were cut and taken to town and back by Messrs George and Alec Ford’s bullock carts. Local carpenters William Winton and John McMann erected the schoolroom of 567 sq feet, costing £160, and the residence, which along with the glebes (the portion of land attached), was valued at £40. It took seven to eight months to build, opening in the spring of 1876 with Mr. William Waddell as first master.

A 3-acre playground formed part of the school area, and an additional recreation ground, which is now under the Parks and Reserves department was created adjacent to the school. At the nor-west end of the schoolroom the ground dipped away, sweeping down to where Pine Hill creek roared its way Leith wards depending upon the rainfall, a happy hunting ground for “Lobbying” during the lunch break. The sou’west wall of the schoolroom contained no windows so the school sat to the sun with the prevailing weather at its back. Although the four many-paned windows in the north and large one in the west wall were set high in the manner of the day, the schoolroom was reasonably well lit and the rise of Pine Hill road enabled pupils seated at the back or near the south wall to see out and keep a check on who was passing as iron clad wheels clattered upon hand sprawled stone of the now metalled road. A large fireplace capable of containing several logs of wood at a time and the doorway were set into the fourth wall. A circular ventilator set in the centre of the wooden ceiling became a natural target for all manner of missiles from ink-soaked wads of blotting paper to pen-speared hair ribbons successfully sent ceiling wards behind the teachers back. In the classroom, pupils sat on backless forms at long desks accommodating five or six pupils as required. These desks were placed on tiered platforms with the primer classes in front at floor level.

Teaching 64 pupils ranging from Primer 1 to Standard 6 in one room must have been pushing on the ability and resources of the teachers and so it became obvious that another room was required. In 1881 a second classroom was added to the existing building at the cost of £61 5s 5d. Mr. Robert Sinclair Gardener was Head Master of the school (1881 – 1888) when the Polish families first came to the district. Mr. Gardener had been teaching in Otago pioneer schools for twenty-three years since his arrival from Edinburgh in 1858. He settled into the School Masters house with his two sisters Miss Catherine and Miss Barbara. Miss Barbara mothered pupils who arrived at school soaked to the skin, comforting them with a hot drink and dried their clothes while Mr. Gardner’s second-best suit made an unscheduled and somewhat unorthodox appearance in school draping the diminutive form of its occupant. The hospital kitchen of the school residence received many visitors as folk stopped to collect mail, rest the horse and exchange news over a cup of tea.

The original Pine Hill School, taken 2015, courtesy of Paul Klemick

During 1888 when Mr. Gardner took ill, Mr. John Kelly became the teacher remaining to the end of the following year followed by Mr. John Harper Moir in 1890. To end the decade Mr. James Smith with his wife and family moved into the Schoolmasters house coming from Glenisla, Scotland and had the distinction of being the first teacher to have children of his own as pupils of Pine Hill School. James Smith continued as sole teacher to an average attendance of 37 until 1893 when Mr. Cornelius Mahoney took over continuing until the middle of 1896 when Mr. Robert Ladreth was appointed in his place, succeeded by Mr. Mangus Thomson in 1899. Then in 1900 came Mr. George William Carrington to the first settled appointment for some years.

As home life was pretty demanding, the children were usually required at home from time to time. The older boys were often required at home, to help trim the tangle of felled forest, gather together the exposed boulders to build into stone walls, clear roots and stumps from paddocks in readiness to receive the plough for the first time, to comb the bush for straying cattle, and look after the increasing dairy herds. Girls needed to cook and care for the smaller children if Mother was sick or abed with the birth of the latest baby, to carry water in from the spring or creek for the day’s cooking and washing, gather wood for the camp oven, trim and clean the kerosene or oil lamps, set the bread to rise and perform the many tasks attending the settler’s household. The Pioneers perforce were practical people, the family working as a unit with a ready hand for any who required help, their requirements for happiness, a home and hard work, a School, and a church. A public library was built, as part of the school, during the 1880’s, where Robert Sinclair Gardner, was the first librarian. He was also responsible for introducing Sunday School.

As the Victorian era was drawing to a close, the roughest of the pioneering days were past although some farms were still being developed high on the hill and the deep gullies.

The sinuous Cowan Road with Saddle Hill in the background, taken 2015, courtesy of Paul Klemick

“RESIDENT MAGISTRATE’S COURT. “Thomas Gdanitz and Joseph Kreft, labourers, Pine Hill, v. John Richards, draper, of George street, Dunedin. and Benjamin Jeffs, labourer, Pine Hill. This was an action, brought to recover from the defendants the sum of £60, for damages done to buildings, fencing, and wood by a fire, which took place on Friday, the 14th October, at Pine Hill, the said fire being caused by the defendants.—Mr Stout appeared on behalf of the plaintiffs, and Mr Macdonald for the defendant Richards.—The plaintiff Gdanitz gave evidence as to the damage done by the fire, and said ho was certain the fire originated on Richards’ land. Benjamin Jeffs was next called, and his evidence went lo show that the property destroyed on the plaintiff’s land was over-valued. He stated that there were several fires, and the timber was in a blaze all over Wood’s property.—ln answer to questions by the counsel for the plaintiffs, witness stated that he was clearing land for the defendant. He would swear that he had not a fire burning on the land he was clearing that morning.—Joseph Kreft stated that the first fire he saw was on Richards’ land. He valued the damage to his property at the same as his partner. He saw the previous witness (Jeffs) preparing the fire by putting wood on the blazing heaps. There was no fire on witness’ property for a week before the fire that took place on Friday, and there was no wood smouldering on his section on the morning of the fire. They tried hard to keep the fire off their (the plaintiffs’) land by throwing water on it. The fire was all over M’Pherson’s section shortly alter 11 o’clock. The shed that was burnt down was worth £10. It was 21ft x 10ft. There were 35 cords of firewood burnt. A lot of other timber was also destroyed. The ground was held on lease from Mr Larnach.—Robert G. M’Pherson deposed that he was a settler, and his land adjoined Mr Richards’ property. He was quite positive the fire came from Richards’. This fire also destroyed a portion of witness’ fencing, and nearly burned down Marshall’s house. He heard one of the men who were engaged in clearing the land say, “There’s a big heap of timber that was standing there this morning all gone. This is better than half a day’s work for me.” —Another witness, named M’Gregor, gave corroborative evidence as to where the fire came from. The track of the fire could be easily traced to Richards’ land.— Another witness, named Dometz, also gave evidence. He stated that he saw the fire burning on Richards’ land near the road.—A Maori named George Pratt, of Waikouaiti, cave evidence as to the wood being burnt. This was the case for the plaintiffs—Mr Macdonald then proceeded to address the Bench, and contended that Mr Richards could not be held liable unless he had ordered the work to be carried out whereby the damage was done. He cited a number of cases in support of this view of the case.—After hearing Mr Macdonald his Worship remarked that he did not think they had time to finish the case, and it was accordingly adjourned till Thursday next.” Otago Daily Times, 29 October 1881, p 3

“A two-roomed wooden house and effects, belonging to Mr Frank Pernisky, were destroyed by fire on Thursday morning at Pine Hill. Mrs Pernisky states that she left the house about 10 o’clock to look after her cows, and had been away about half an hour when she heard her mother-in-law calling out “Fire!” and on hastening back found the place in flames. Mr Pernisky, who was cutting bush in the vicinity, returned to the house, but was unable to do any good. Mrs Annie Pernisky was the first to discover the fire, and states that the flames were then breaking through the side of the building near the chimney, which it is thought was faulty construction. The building was insured for £70 and the effects for £30 in the New Zealand office, but the estimated value of the property is £20 above these amounts.” Otago Witness, 6 July 1889

“ORDINARY MEETING. Petitions. J. Konkel and four other ratepayers in the Pine Hill district petitioned the council to have about 11 chains of road at Wahles Hill (Pine Hill district) metalled.— Referred to the inspector for a report as to what the settlers would do themselves towards effecting the work asked for.” Otago Witness, 3 December 1891, p 20

“Waikouaiti County Council. Contracts. Reporting on the petition of Mr J. Konkel and others, asking for a piece of road formation between sections 47 and 53, North Harbour and Blueskin district, the inspector stated that the petitioners had done some formation which it would be necessary to go over again before metal is put on. This was the only outlet these people had, and until a month or so ago they had to sledge everything to and from their properties to the road. The petitioners were willing to supply the stone if the council broke and spread It. The Inspector was instructed to call for tenders for the formation of the road, and breaking and spreading of metal thereon as soon as the settlers interested supplied the necessary spalled stone in such places along the road as the inspector may direct.” Otago Witness, 22 December 1891, p 29

“Another fire tragically claimed the life of Margaret Nora; Margaret Perimystery, aged 17 months, died from severe burns received on May 6th. The mother was milking the cows at Pine Hill, and left the child in bed, where its nightdress caught fire.” Otago Witness, 18 May 1893

“Wandering Cattle.—Antony Perniski, for allowing five head of cattle to wander on the Leith Valley road, was fined 4s; and John Roy, for allowing five head to wander in High street. Maori Hill, was fined 10s.” Evening Star, 28 March 1899, p 2

In 1908 saw the introduction of the three-term break rather than the two term year with Summer and Winter holiday breaks only, which had been standard practice since the school began.

Until 1913, most finance raising functions for the school were the several-a-year Concert with Dance to follow held in the big class room attended by folk from afar riding or driving up the hill for an evening’s entertainment, in spring-buggy; dogcart; dray or horseback. The horses had the comfort of a nosebag of chaff whilst awaiting the journey back home, tethered around the playground, where Mr. Robb boiled the copper to make the supper tea supplemented by water from the black iron kettles balanced between logs boiling merrily away in the small classroom fireplace. Supper served, the concert seats set back in the bottom wall-cupboard beneath the library, horses checked and the copper-fire doused, then the fiddle and accordion of August and Frank Konkol would strike up calling partners for the “first set” and the sound of music and merriment issued from the little school. These dances were justifiably popular and were attended by members of the whole family, baby comfortably cradled upon a pillow in an upturned form.

Children and young adults partnered parents, relatives and neighbours as they showed progress made at Mr. Robb’s Saturday dancing classes held in that same room while he took turn on the accordion.

Many picnics were held in the top flat paddock in Campbells Road by favour of various owners until mechanised forms of transport increased the picnics range to further a field.

And so was the life of the small tightly knitted community until the advent of the First World War.

Location of Polish Settlers at Pine Hill in the North Harbour & Blueskin District, courtesy of Google Earth

Polish names associated with early Pine Hill are: Gdaniec (Danitz), Kąkol (Konkel), Kreft, Piernicki (Perniskie) and Plew.

Resources;

Templeton C. T (2016) Microsoft Word – St. Joseph’s Catholic Cathedral Dunedin.docx (nzopt.org.nz)

Compiled by Paul Klemick (2022)