Plewa family

click on name or picture to go to Plewa Family Tree at ancestry.com

Click ship to open the Palmerston ship page

Spoken Polish

If you would like to hear the Polish names and text spoken in Polish then we can help.

Firstly click on this link "Text to Polish" and then copy the text you wish to hear, and paste it into the translation box. You can either listen to it or have it download onto your machine.

Enjoy !!

SURNAMES & THEIR ORIGINS

KOCHANSKI (Pol) kochac. Meaning: to love or (Ger) koch – cook. Also from the topographical place: Kochanow.

KOSTKOWSKI (Pol) kość. Meaning: bone.

LEWANDOWSKI (Pol) lawenda. Meaning: the lavender bush.

PLEWA (Pol) plewa. Meaning: husk, shell.

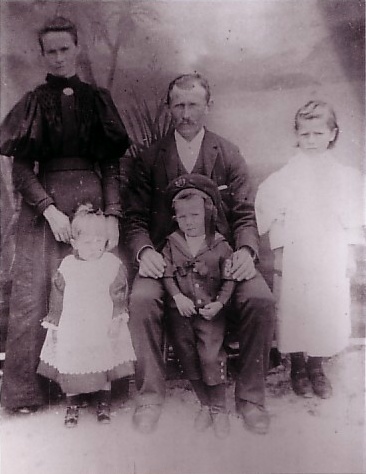

August Plewa, a platelayer (b. 1847–d. 1913) was born at Szczerbęcin on 22 November 1847, the son of Franciszek Plewa (b. abt. 1820–d. 1876) and Franciszka Kochanska (b. 1817–d. 1872). August married on 16 August 1868 at St. Małgorzata in Miłobądz to Franciszka Weronika Kostkowska (b. 10 March 1839 at Knybawa–d. 1934), the daughter of Jan Kostkowski (b. 1792) and Maryanna Lewandowska (b. abt. 1805–d. 1850). The family born at Mieścin were: Franciszek (b. 1869–d. 1916) and Angelika (b. 1871–d. 1941). In Poland, August worked as a platelayer on the railway line between Starogard Gdański and Tczew, which opened for service on 16 January 1871. They family left the village of Mieścin for Hamburg where they set sail aboard the Palmerston on 29 July 1872, arriving at Port Chalmers near Dunedin on 6 December 1872. However it is interesting to find a later entry on one of the children’s baptism records where the priest has noted Amerika 1872.

Listed aboard were: August Plewa age 24, Francisca 31, Franz 2 and Angelica 6 months. The family was sent south to Scroggs Creek on contract work with Brogden and Sons to lay the southern railway through the Taieri.

“R. W. Capstick reports having sold, on Monday, the 14th inst., at noon, on account of the Waste Lands Board, the following township and rural sections; — Township of Waihola. August Plewa. Block XXI sections 10 & 11 at £3 each. Waihola (From our own correspondent) Nearly the whole of the land in the Waihola Hundreds except the bush reserve is now in the hands of private parties. There appears to have been quite of late a mania for land in this district, from rough hilly blocks of two or three thousand acres, to quarter acre township sections, some of the latter fetching very good prices considering their situation.” Bruce Herald, 05 August 1873

The family moved first to Waihola then south to Akatore where August built a sod cottage. Here he worked for Mr. Wayne as a farm labourer. The family were: Johann Patrick (b. 1874–d. 1940), August Michael (b. 1875–d. 1935), Joseph (b. 1878–d. 1944) and Julius Thomas (b. 1881–d. 1954). According to the 1882’ Return of Freeholders, August owned two acres to the value of £100 at Akatore. They moved to Milton where August worked as a labourer and was naturalised as a New Zealand citizen on 15 September 1887. During one of the big floods, August and Frances were marooned in their house in Albert Street upon the kitchen table until a rescue party arrived.

August died at Milton on 20 September 1913 aged 65.

Bruce Herald, 4 July 1907, p 5, paperspast.natlib.govt.nz

“100 Not Out!” Milton’s Centenarian. As announced in last issue, Milton’s oldest inhabitant—Mrs August Plever, of Cargill Street—celebrated her 100th birthday on Thursday and was the recipient of congratulatory messages and telegrams in honour of the important event. The Governor-General (Lord Bledisloe) telegraphed “I send you warm congratulations and good wishes on the attainment of your hundredth birthday, and trust that you are still keeping well.” The Premier (Mr G. W. Forbes) wired; “Accept my hearty congratulations and good wishes on the celebration of your 100th birthday. May you enjoy many more years of good health.” A telegram from Mr P. McSkimming, M.P., read: “Hearty congratulations on your 100th birthday. May God’s blessing rest upon you. Sincerely trust that your lum will keep reeking for a wheen yet. Kind regards.” In celebration of Milton’s first centenarian a happy birthday party was held at Mrs Plever’s residence on Thursday evening and attended by large number of relatives and friends. Amongst those present were the Mayor and Mayoress (Mr and Mrs Jas. Gray) and W. J. Cockburn. The mayor extended official congratulations to Mrs Plever, and in happy speech on behalf the Council presented her with a handsome eiderdown quilt. Earlier in the day Mr D. McGregor (chairman) had personally conveyed official greetings from the Bruce County Council. The birthday cake was surmounted with its hundred candles, which were lit by the honoured guest. A happy evening was spent in vocal solos and community singing. Despite her advanced years Mrs Plever enjoys good health, and was able to take active part in the birthday festivities, at which she sang two songs in her native Polish language. Although official records have become mislaid with the passing of the years, it is authoritatively stated that Mrs Plever was born at Gorshaw (Poland) on March 10, 1832, her maiden name being Frances Coskoviski. When about twenty-seven years of age she married Mr August Plever in her native country. About ten years later they emigrated to New Zealand, accompanied by their young family. They journeyed per the ship Palmerston, which arrived at Port Chalmers in 1872. The husband was a railway platelayer in his native country, but in New Zealand carried out general farm labouring occupations. They took up residence at Waihola, afterwards removing to Glenledi, where Mr Plever worked for the late Mr Wayne, and he built a clay whare on the site where Mr D. Gardyne’s home now stands. From Glenledi Mr and Mrs Plever removed to Milton, where Mrs Plever has since resided for about half a century. Her husband predeceased her almost ten years ago. She has surviving family of four sons and one daughter—Mrs A. Anicich (Milburn), Jack (Melbourne), August, Joseph (Milton) and Julius (Timaru). During the big flood in Milton about ten years ago Mr and Mrs Plever were marooned in their house at southern portion of Albert Street and had to spend the night uncomfortably seated on the kitchen table until a rescue party arrived. Possessed of all her faculties and able to walk without a stick Mrs Plever thoroughly enjoyed the festivities arranged in her honour. During her lengthy life Mrs Plever possesses the unique record of having journeyed only twice in a railway train—once on visit to Dunedin and the other occasion the three-mile journey from Milton to Milburn. She has made five trips around the district in motor cars.” Bruce Herald, March 1932

Francisca died at Milton on 7 September 1934 and a Requiem Mass was held at St. Mary’s church in Milton. She was buried with her husband at the Fairfax Cemetery near Milton.

Bruce Herald, 6 April 1911, p 1, paperspast.natlib.govt.nz

“OBITUARY. MRS FRANCES PLEVER The death of Mrs Frances Plever, which occurred at Milton yesterday, removed the oldest inhabitant of the district, and one of the oldest in New Zealand. Mrs Plever was in her 103rd year, and on March 10, 1932, when she reached the age of 100 years, she received congratulatory telegrams from the Governor-General (Lord Bledisloe), the Prime Minister (Mr G. W. Forbes), Mr P. M’Skimraing, M.P., and several others. She was also the recipient of many personal congratulations. Until recently Mrs Plever had resided with one of her sons but was lately admitted to the Milton Hospital. Although official records have been mislaid with the passage of time, it is stated authoritatively that she was born at Gorshaw (Poland) on March 10, 1832, her maiden name being Frances Coskoviski. When about twenty-seven years of age she married Mr August Plever. in her native country, and about ten years later they emigrated to New Zealand, accompanied by their young family. They arrived at Port Chalmers by the ship Palmerston, in 1872. Mrs Plever’s husband was a railway platelayer in his native country, but after arrival in the dominion he engaged in general labouring occupations. They took up their resident at Waihola, and afterwards removed to Glenledi. From the latter place Mr and Mrs Plever went to live at Milton, where Mrs Plever had since resided for over half a century. Her husband predeceased her about thirteen years ago, and she is survived by a family of four sons and one daughter.

Possessed of all her faculties and even able to walk without the aid of a stick after attaining her hundredth birthday, Mrs Plever thoroughly enjoyed the festivities arranged in her honour, and sang two vocal solos in her native tongue. Though resident only thirty six miles from Dunedin, it is surprising to record, in these days of modern fast transport, that Mrs Plever had only once travelled by train to the city in the whole course of the sixty-two years since her arrival, and her only other trip by train was the three-mile journey between Milton and Milburn. Her trips by motor car around the Tokomairiro district were also very limited in number.” Evening Star, 08 September 1934, p 12

Francis Martin Plever was born at Mieścin on 15 October 1869. He married in 1900 at St. John’s in Milton to Annie Pearson (b. 1869–d. 1934), the daughter of John Pearson (b. 1834–d. 1917) and Jane Abercrombie Brookes (b. 1851–d. 1940). At Milton they had a son, Frank (b. 1900–d. 1959).

“Bruce Licensing Petition. THE MAGISTERIAL INQUIRY. The inquiry into the allegations contained in the petition to have the Bruce licensing poll declared void, was commenced before Mr G. Cruickshank, S.M, at the Courthouse, Milton, yesterday. Messrs P. R Chapman, W. A. Sim, and D. Reid appeared for the petitioners, and Messrs A. S. Adams and J. F. Woodhouse appeared on behalf of Jas Blaikie—au elector. Great interest was taken in the proceedings, the Court being crowded all day. Mr Chapman, in opening the case for the petitioners, said the petition had been lodged under the Regulations of Local Elections Act, 1876. Numerous grounds were advanced upon which the order of the court was being sought to declare the poll void. The petition contained several allegations some of which had been further particularised in a memo, sent to the opposing counsel. In the main, the causes of the complaint on which the’ petitioners relied were of two classes… Annie Plever stated she was partially blind. She resided at Akatore and had recorded her vote at the Akatore Beach booth Mr Milne and Mr Green and her husband were present when she voted. Witness only asked Mr Milne to assist her. Mr Adams: Mr Milne was deputy returning officer. Frank Plever, husband of the last witness, said Mr Milne asked his wife how she wanted to vote Witness told him ” Continuance,” and then Mr Milne said, “Is that right?” Mrs Plever said “yes,” but witness thought only one stroke had been put on the paper. Witness voted in the open room… The enquiry was adjourned ab 4.30 p.m. till 11 a.m. to-day.” Bruce Herald, 27 January 1903, p 5

Frank worked as a farm labourer at Glenledi and died in Dunedin on 30 December 1916 aged 47. Annie died in Milton in 1934 and both are buried at the Fairfax Cemetery near Milton.

Angelica Anicich (nee Plevenski), Antonio Anicich and family

Angelica (Ellen) Plevenski was born at Mieścin on 19 December 1871. She married on 12 June 1889 at St. Mary’s in Milton to Antonio Anicich (b. 1862 at Fiume, Croatia–d. 1945). The couple moved to Melbourne in Australia and according to the 1891 Victoria Rate Books, they settled at Gladstone Place in South Melbourne. Here they gave birth to Mary Theresa (b. 1889–d. 1975). Antonio worked on the wharves at Melbourne for four years before returning to New Zealand where he took up farming at Akatore, then at Circle Hill, and later at Milburn. The family born at Milton were: John Francis (b. 1894–d. 1983) and Margaret (b. 1896–d. 1964), at Akatore; Teresa Ellen (b. 1899–d. 1980), at Waihola; Joseph (b. 1901–d. 1966), at Akatore; Antony Augustine (b. 1903–d. 1986), Julius Martin (b. 1904–d. 1978), James Albert (b. 1906–d. 1966), at Milton; Michael Raymond (b. 1908–d. 1981) and Edward Luke (b. 1910–d. 1995).

“GLENLEDI. Dance. On the 21st ult. Messrs Plever Bros. gave a very enjoyable dance at the residence of Mr Annisetch, Akatore. A large number of visitors were present from the surrounding districts. The music was supplied by Messrs Orlosky and Reikowski, while Mr Julius Plever made a most efficient M.C. During the evening songs were sung by a number of visitors present.” Otago Witness, 11 November 1903, p 31

They always took part in various activities in the district where Angelica was secretary for the Milburn P.W.M.U. and also a member of the Milburn W.D.F.F. Ellen died at her residence on Park Farm at Millburn on 10 January 1941 and Antonio died at Milton on 10 October 1945. They are buried together at the Fairfax Cemetery near Milton.

“OBITUARY. The sudden death of Mrs Ellen Anicich at her residence, Milburn, on January 10, at the age of 70 years,, removed an old and highly-esteemed resident of the district. She was born in Poland, and when an infant came to New Zealand with her parents, Mr and Mrs A. Plever. They settled at Waihola, and later removed to the Tokomairiro district, and deceased had resided there ever since, with the exception of four years spent in Australia. She married Mr Antonio Anicich 52 years ago, the Rev. Father O’Neill performing the ceremony in St. Mary’s Church, Milton. The late Mrs Anicich had many friends, and was an ardent supporter of the Roman Catholic Church. She is survived by her husband, three daughters, and seven sons —namely, Mesdames W. M‘Kay (Pigeon Bay), W. Taylor (Christchurch), D. Jensen (Milburn), and Messrs Joseph and Raymond (Waimate), Edmund (Dunedin), John, Anthony, Julius, and James (Milburn).” Evening Star, 16 January 1941, p 8

“Recollections” by John Jensen;

“EARLY DAYS:

As I have mentioned, my maternal grandmother was Polish, At the age of six months, she arrived with her parents on the Palmerston at Port Chalmers in 1872. You may have seen an article about that event in The Mix (27 Nov).

My Uncle Bill and Dad (Dave) took over the farm at Milburn in the 1920s. My father and mother, Teresa (Tessie) raised a family of three, while Uncle Bill and Aunt Lilly had four children, three daughters and a son.

I well remember how the eldest of Uncle Bill’s family, Marie, liked to organise us all as a ‘scout’ troop. She was very forthright. She recalled years later that I did not readily fall into line; a stubborn streak showed up early in the piece!

Dad did most of the cultivation work, with a team of draught horses. It was very hard work, especially for Dad who suffered from a bad back and a knee that eventually required surgery. Even harnessing the horses in the mornings and reversing the process when he came home must have entailed much effort – the harness was very heavy. And it was hard for the horses, that made for the creek at day’s end as soon as they were relieved of their harness.

Horses provided the energy to do much of the farm work – pulling the binder to cut grain, scuffling the turnips and potatoes, and pulling the dray. (However, after Dad gave up the farm – Uncle Bill stayed on – a tractor was acquired!)

There were three plantations of bluegums on the property. From time to time one was felled for firewood. This was extremely hard work, Uncle Bill and Dad using a cross-cut saw to fell a tree and to cut the trunk into manageable lengths. The thickest were then split with a blasting gun. (I remembered how this was done, and did likewise when I bought my own farm at Highcliff years later, and again on our Dukes Rd property.) A circular saw, operated with a long belt driven by an petrol-powered motor, was used to cut the lengths of wood into blocks.

Giving a small boy ownership of five rabbit traps must have been a leap of faith for my father, as a trap can be a rather dangerous piece of equipment. I used a stick to position the ‘tongue’; a serious trappers would use his forefinger. But one day my luck ran out, the jaws of the trap catching the little finger of my left hand. I remember which paddock I was in, and how I ran home in distress, blood dripping.

I hated finding a possum in a trap. The vicious hissing scared me, and I had to call on my father to deal with the animal. Catching a ferret was also not welcome, although at least the skin could be sold for a good price.

Dave and I were in our element taking part I farm activities: making stooks with sheaves of wheat or oats, watching the chaffcutter at work, helping bale wool at shearing time and catching lambs during ‘tailing’.

As well as koura, the creeks provided eels – silver-belly and long-fin. We made a trap out of bird netting, with a rabbit carcasse as bait (made very smelly by part-roasting it on a gorse fire). After placing the trap in a sack, we laid the trap, with the opening facing down stream, in the creek. Silver-belly eels were good eating, although difficult to skin.

Our combined families raised a pig every year. When the pig was slaughtered there was one part we liked to get our hands on – the bladder, which we would inflate and use it as a football. Another no-cost way of amusing ourselves. The (very coarse) hair of the animal was scraped off, after the carcasse was dunked in hot water. Most of the meat was made into bacon or ham.

Once a week the Milton baker, ‘Doughy’ Anderson, called in his van. During school holidays we liked to be nearby, because Mr Anderson always handed all kids present a yeast bun – fresh and delicious! A butcher also called; Mum would buy sausages, tripe, corned beef, etc, but not mutton or lamb, as these were routinely killed on the farm and shared between the two families. We did not have a refrigerator, so a lot of meat was eaten in a short time. Rabbit meat was also often on the menu.

Milburn School was almost two miles away, on the Dunedin – Invercargill main road (unsealed). For the first year I walked, but then progressed to a bike. Small bikes were not available then; mine was a lady’s bike – I would have been too small to manage one with a bar. In winter, when frosts could be severe, we kept our hands warm by having rabbit skins, turned inside out, covering the handle bars.

I have clear memories of school milk. Every morning a truck dropped off a crate of half-pint bottles with cardboard tops. In those days homogenised milk was unheard of; the cream rose to the top, meaning that the bottle required shaking. In the winter months, when the classroom was heated – by a Romesse stove -our junior room teacher, Miss Smart, had the crate of milk placed in front of the stove. No doubt she thought that this would help warm us, but we preferred it cold; to question the teacher’s decision was unthinkable.

During WW 2 the export of New Zealand fruit was disrupted. Surplus apples were distributed to schools. At Milburn these were usually Jonathans, which arrived in boxes, individually-wrapped in tissue paper, The apples and milk undoubtedly helped keep us healthy!

Another health service was school dental treatment. For this we travelled to Milton, where the nearest clinic was located. A t rip to the dental nurse struck fear into us: Being operated by a treadle, the drill was slow, and therefore very painful. I was deemed to have too many teeth, so had four molars extracted. I felt the pain for years afterwards!

World War 2 began shortly before my eighth birthday. I recall how we listened intently to the daily British broadcasts which described the progress or otherwise of the Allied forces. The Auckland Weekly was closely perused. It showed photos of NZ soldiers, sailors and airmen: Killed in action, Wounded, Missing in Action. I found it all very, very sobering.

Some of my cousins (much older than I) and a cousin’s spouse were among those sent overseas. My mother would write to them and receive letters in return. She also sent food to them. She used an ingenious method of sending meat. Rolled beef, mutton or lamb was skewered and placed in a large golden syrup can, the skewers keeping the meat off the sides. She then poured molten fat into the tin, completely enclosing the meat. Dad soldered round the top of the can, making it airtight. Finally Mum sewed mutton cloth over the can. I do not recall the method of dispatch.

I recall clearly the announcement that Germany had invaded Russia We were sitting around the kitchen table, all ears for the news on the radio. I remember clearly the words “Russia and Germany are at war.” This development was seen as taking the pressure off the Allies.

Cousin Marie had her ‘troop’ (us) dig a trench in one of the plantations, in case of Japanese invasion. It remained for years afterwards.

BURNSIDE:

With an acre of land adjoining the house section, there was room to maintain a measure of rural life. We kept a cow, chickens and a pig. In time I was old enough to take a turn milking the cow, and was not impressed when the Ayreshire that replaced an older animal managed to put its hoof in the bucket of milk, or chose milking time to move its bowels! Some of the milk was left undisturbed for a day or two so the cream could rise to the top; it would then be scooped off and either made into butter or inserted in Mum’s famous cream sponges. Turning the handle of the churn was a job I could not escape; I longed for the ‘thump, thump’ which signalled the eventual formation of butter. Mum made the butter into ‘pats’, which were either used at home or sold to the local storekeeper. Surplus eggs went either to friends or the grocer’s shop.

When wartime rationing was introduced we were not badly affected, as we produced all of our butter and eggs, and had meat sent from the farm at Milburn.

From Burnside Dave and I attended St Francis Xaviour’s in Mornington (St 4, Foprm 1 for me). The nuns gave us an excellent grasp of the structure, grammar and other conventions of English. The 1961 syllabus watered down the curriclum, leading to widespread lowering of standards. As I listen to the likes of TV 1 and National Radio, I wonder what some broadcasters and politicians (even high-profile MPs) were taught at school! I cringe when I hear the mispronunciation of many words: been, hours, congratulations, not at all, ability – to name just a few.

We then went to CBHS, now Kavanagh College. My strengths were mathematics and Latin. The structure of Latin appealed to me.

We travelled by train, as did many others from Mosgiel, Green Island and Burnside. On the train boys and girls were segregated. But some of the more desirous of contact with the opposite sex communicated by leaning out the windows and shouting to their boyfriends and girlfriends. They were not too popular when they were slow to shut their windows as the train entered the Caversham tunnel, letting in clouds of unpleasant and unwanted smoke!

The old Caversham-Burnside tunnel was open for public use in those days. We would bike through it, sometimes rubbing against the sooty walls. Dave used the tunnel daily, when he was apprenticed to a grocer at Forbury Corner.

ST ANDREWS:

I took over my first class as a probationary assistant in 1951, at the tender age of 19 years 3 months. I did not find the experience daunting, even though my classroom was the Anglican Church hall, about 100 metres from the School itself. As the head teacher had a class full time, he rarely visited my classroom: looking back, I think he must have been happy with how I was coping.

With just small windows on the north-facing wall, the hall was very cold. My first task on arriving on winter mornings was to light the Romesse stove, sometimes blackening my clothes in the process.

MIDDLEMARCH:

There was a great community spirit on the Strath Taieri, so I thoroughly enjoyed my time there. There were well-established families: notable family names included Thomson, Jones, MaAtamney, Moynihan, Howell, Elliot, Matheson, Keast, Beattie, Roberts, Rebwick and Robertson. Almost everyone in the community pitched in, one way or another, for the famous strath Taieri A and P Easter Show. This was the event of the year, but I think it is no longer held.

At that time the government-funded adult education. This included choral singing. There was a choir at Middlemarch, with quite a number of members, some of them very talented. I joined, of course. Concerts were well attended.

When living alone one needs to cook. Thanks to my mother, I learned to do this well enough. I had a small coal range and a very slow, small electric oven. The coal range was excellent. It keep me warm, but it was also great for baking scones. When we had a ‘home’ tennis match, we provided afternoon tea – a country tradition. Of course I took along scones, which became my trade mark, and they went down well. Dinner at night included puddings – steamed jam pudding and baked apple roll being favourites. These I would cook on a Monday, and each would last a week!

Although I know very few people in Middlemarch today, I still feel that I am a ‘local’!

COUTSHIP AND MARRIAGE;

In 1957 I met Patsy O’Callaghan through badminton. About July we got engaged and an engagement party was held. The very next day Patsy was rushed to hospital, suffering from tuberculous peritonitis. Emergency surgery took place: it was a knife-edge situation. When Patsy was out of danger she was told that she could forget about being able to bear children. The doctors were proved wrong.

By December she had recovered and we married just before Christmas. In 1959, against the odds, Gillian was born, Simon following in 1961. Two healthy children had been born, both to become very high achievers at school, university and beyond.

SCHOOL CHOIRS:

At Wakari School, where I was a class teacher from 1956-61, two people on the staff were very strong in music. But in a short space of time, both left, meaning that there was no one to lead the school choir. This was unfortunate; school music festivals had a very high profile in Dunedin at that time. The principal, Ted Darracott, surprised me by asking me if I would take charge of the choir. This must have been a gamble on Ted’s part, because, to my knowledge, he had not even heard me sing! I saw this as an opportunity, and accepted on the spot.

I took cues from the maestro Val Drew, who was such an inspiration. Two months later I was standing in front of my choir at the Dunedin Town Hall, conducting for the very first time in public. I was extremely nervous, my knees shaking so much that I could well have been seen as conducting with my legs!

I carried on with school choirs at Otekaieke and Weston, thoroughly enjoying the experience. Primary school festivals at the Oamaru Opera House were big events in those days; teachers, parents and grandparents took great pride in their children’s performances. It was immensely satisfying seeing the glow in the choir members when they the audience reacted enthusiastically. I tried to select songs with a twist, that were fun and challenging for the singers. Favourite songs included Pedro the Fisherman, The Computer, The Changing of the Guard, The Holy City, Ma Belle Marguerite and The Pirates’ Christmas. I was fortunate in always having excellent accompanists: Moira McDonald at Wakari, Wendy Bayley at Otekaieke and Noni Wells at Weston.

OTEKAIEKE :

I took over a school in good heart, with very good standards academically, culturally and in sport. The success levels when the pupils went on to secondary were generally high – evidence that small schools can succeed as well as, if not better than, large ones.

I resumed my interest in tennis, playing in the Otekaieke team and acting as secretary of the Lower Waitaki Sub-Association.

An Adult Education choir, with the same director that we had at Middlemarch, was another interest.

WESTON DAYS:

Weston School was comprised of five classrooms when I arrived in 1968. The township grew steadily, to a maximum of eleven classrooms, meaning I was able to stay for quite a long time – 19 years. Up until the time that there were seven or eight classes I was full time teaching. Unlike today, there was no release time, so it was very hard work: as well as teaching a class of about 35 I needed to know how the rest of the school was going and keep up with administration, school committee matters and the functions of the home and school association. At times I was on the brink of burn-out.

Over the years I became convinced that ‘telling’ and ‘teaching’ are not synonymous. A good teacher is, rather, a facilitator. Children need to have ownership of what they are doing, and learn form each other. Arousing their interest is paramount. They need to satisfy themselves, not just the teacher. The teacher also needs to trust his/her pupils. With these principles in mind, I was able to leave my class for quite long periods; I would walk out of the classroom without telling them I was going, and when I came back they were so engrossed in what they were doing that they sometimes did not notice my return.

Eventually I became a ‘walking’ principal, which meant a lightening of my work load, but without the satisfaction of having my own class.

Overall, my time at Weston was immensely fulfilling.

With my Forms 1 and 2 class, I continued the practice of taking a school camp and other outdoor education venture on alternate years.

The camps took place at three venues: Camp Iona near Herbert, Camp Armstrong at Inch Valley, and Pounawea. Experiences for the children included camp-outs, abseiling, archery, kayaking and science studies. For most camps I was the only teacher from the school, so they were quite hard work. But at Pounawea it was possible to have David Atkinson’s involvement. David was very competent at teaching all the activities, especially kayaking.

Up until the early 70s an overnight ferry operated between Lyttelton and Wellington. It was possible to take school groups to the capital without having to find overnight accommodation. We would leavet Oamaru by train about 1.30 pm, take the ferry overnight, spend the day in Wellington and return by ferry the next night. A highlight in Wellington was Parliament, so before and after the trip the pupils became quite politically-aware. They were not impressed with the way that some members behaved in the House!

Our trip to Wellington in 1969 was problematic even before we left home. On the day and night before, a southerly squall hit the South Island. It was still snowing on the morning of departure day. Memories of the Wahine Disaster the previous year were still raw. What were we to do? I made contact with Metservice throughout the morning, trying to decide whether to go. The pupils were waiting in the classroom, all packed, waiting for the verdict. Finally, about 11.30 am, it seemed OK to give the go-ahead. Just two hours later we were on the train.

That night the sea was still very rough, and it was not long before some of the children became seasick. Two, in particular, took most of the following day to recover, so did not get much out of their Wellington visit!

Back in the classroom, much purposeful follow-up activity arose. A presentation for parents included a mock session of Parliament. A few of the pupils emulated the behaviour of real parliamentarians!

Talking of parliamentarians, the school magazine, The Comet, offered the pupils opportunities to interview some well-known people. These included Prime Ministers Robert Muldoon and Bill Rowling, as well as Fred Dagg. The pair who interviewed Mr Muldoon did so in his official car, on the way into Oamaru from the airport.. It was all recorded on a tape recorder and written up later. Those pupils will never forget, I am sure.

The school environment today is very attractive, with new, well-designed buildings and attractive plantings. So much better than the typical Otago Education Board designs of the 60s.

When I arrived in 1968 the main playing field was very exposed to the north-easterly winds that were prevalent in the spring months. I felt that at that time we needed to do something about that; with the support of the Weston Progress League and School Committee cedars were planted. I was delighted to see how well they had flourished, and how much more sheltered the playground is now.

I got involved in junior tennis, serving several years as chair of the sub-committee of the North Otago Tennis Assn. We ran tournaments for primary- and secondary-aged players, as well as representative matches. At Weston School I coached a large bunch of pupils, and at one point had seven teams in the Saturday morning inter-club competition. I was president of the Weston Tennis Club for several years, and played in the afternoon interclub competition.

I also joined the Progress League, being chair for a term.

WAKARI SCHOOL:

Wakari was my last appointment before retiring. It was great to be back at the school, which has had an excellent reputation over many years. ”

David Lange had recently dictated that education boards would be disestablished and schools would become self-governing. School boards of trustees would be set up. Every school would be expected to have a mission, sets of principles, policies, job descriptions as well as a raft of other requirements.

As principal, it was my responsibility to guide the changes. This was a new challenge. Lange decided that the process was to be completed withing eleven months. That would not have been too demanding if left to just myself, without consultation. But it was imperative to make it inclusive, with everyone affected having a sense of ownership.

At this time I knew little about how to use a computer. I therefore wrote everything long-hand, which meant much time at my desk. This job fell to Julie Knudson, our very efficient, competent, obliging and long-suffering secretary.

One of the positives about Tomorrow’s Schools was that the principal was able to select his/her own staff. I felt it important to involve other senior staff, so that’s what we did. I took pride in appointing excellent people. Prior to Tomorrow’s Schools a school just had to accept an education board appointee.

One of the negative changes was the demise of the school inspectorate and teacher advisory services. Teachers, and consequently pupils, had benefited immensely from their expertise.

EARLY RETIREMENT YEARS:

I retired at the end of 1992. It was quite a wrench, after 44 years. Patsy and I had settled down on a 3-acre farmlet in 1989, and I was heavily into bowls, so there would be plenty to occupy my time.

We owned a caravan, in which we set off on a holiday to Nelson/Marlborough in February 1993. On our way home, on 1 March, we stopped off in North Oamaru. There, while crossing the main road, I was knocked down by a motor bike. I have no memory of the event or what happened after it. I regained consciousness in Oamaru Hospital for about a minute, to hear a nurse say, “You are in hospital, Mr Jensen. You’ve got a broken leg.”

I regained consciousness several hours later, in Dunedin Hospital, with an external fixator in my leg. This device consisted of four metal ‘pins’ each nearly 10 com long, sticking out of my fibula , and a series of bars connecting them, parallel to my leg – a bit like scaffolding . The surgeons had identified 50 pieces of bone, before giving up counting. I had also lost two teeth and the left side of my head was numb. Further surgery followed later.

My recovery was long and tedious . But I was determined that this interruption was not going to stop me doing things. For example, I wanted to continue gardening, and devised innovative ways to get to my vegetable patch and carry my tools with me. I was diligent with my physiotherapy programme. At last, after 340 days, I was able to drive again.

I have had after-effects. A few years ago, because my leg was a little out of alignment, my knee need replacing. A replacement hip followed two years after that.

Part of my therapy in 1993 was taking up hand-craft pottery, at the Mosgiel Abilities Resource Centre. When I got back to normal, I offered to help in any way that I could. A short time later I was invited to join the board; after a few meetings I was asked to take the chair – back in a ‘hot seat’ again. The organistaion was going well, but we realised that structure was need. My Tomorrow’s Schools experience came in handy, as we tasked ourselves with writing policies and job descriptions. I stayed on as chair for seven years, and subsequently was awarded life membership.

In 2002 it became clear that Patsy had a battle ahead of her with breast cancer. It was my turn to become the carer. Instead of trips to Dunedin Hospital’s Orthotics Department, we made numerous visits to Oncology. The last 19 months were particularly taxing for Patsy. Fortunately I had fully recovered and was able to do the required nursing, cooking, etc. When the cancer spread, it was obvious that the disease would not be beaten. In January 2005 Patsy passed away at the Dunedin Hospice.

In the years following I had a couple of challenges.

The first followed the flood in 2006. The Otago Regional Council considered how to solve the flooding problem. One of their senior engineers had a plan, which I heard about through a neighbouring couple. In the next day or two the engineer was to put this plan to Council. He was proposing that bunds be put in place around our houses and all hedges be removed. This, to me, was unthinkable! I had a 100m+ macrocarpa hedge along my southern boundary, and its removal would have ruined my property This daft scheme had to be stopped in its tracks. I contacted a local councillor and asked him if he would come to a meeting in my driveway the following day, and then rang all 20 of my neighbours who would be affected. Only three households were not represented. I invited all to have their say, while the councillor listened attentively. We won the day, and the scheme was dropped.

The second was a contest between ACC and me. On the road line outside my former property there is a deep drain. I dropped into it one day to remove some rubbish. While exiting I tore the Achilles tendon on my good leg. ACC provided assistance for medical and physio appointments, but when a surgeon applied for funding for surgery, ACC changed tack, saying that the injury was a result of my age; I would not be entitled to funding. I knew this to be wrong for three very good reasons . I went to Review, and was turned down. I then went to Appeal. Time passed and my symptoms diminished. I was able to go on an overseas trip. On my return a large volume of mail awaited my attention. One letter was from the Justice Department; would I please attend a hearing at the Dunedin District Court – the following day! By this time, surgery was not needed, but, jet-lagged as I was, I turned up. I wanted to win this one. In the court room there were four people: the judge, his assistant, the ACC lawyer, and me. I put my arguments, and the lawyer presented ACC’s. Several weeks later I received a letter saying, in effect, that I had won!

Two wins to John.

A HORROR YEAR:

In February 2018 cancer struck again, this time at very short notice. Shirley, my very close friend and travel companion over eleven years, was admitted to hospital in late January. She was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and died less than three weeks later. Shirley had been so dear to me and I was devastated – it was so unexpected.

Two months later my brother Dave suffered a massive stroke and never recovered. Dave and I had been best mates all our lives; he had been so considerate, good-natured and even-tempered, never speaking an ill word of anyone. Now he, also, was gone.

I the space of a few weeks a huge void had been opened up in my life, a situation that I took quite some time to come to terms with.

RECENT TIMES:

I sold the Dukes Rd farmlet in 2015. The work was getting too hard, and I wanted to take things a bit easier. Unable to find a Mosgiel house that suited me, I bought a section and built a new house. I am still able to follow my gardening interest: as well as vegetables I grow flowers, shrubs and fruit (14 kinds). The house is warm, comfortable and convenient. But as the outside wok is rather demanding now so I am considering moving again, to a retirement village.”

August and Frances Plever and Francis Plever. Block 11 Plots 129 & 130 at Fairfax Cemetery near Milton

References

Pobόg-Jaworowski, J. W, History of the Polish Settlers in New Zealand, ed. Warsaw; Chz “Ars Polonia.” 1990, pages 23 & 170.

Research Sources

Archives New Zealand, Passenger Lists, 1839-1973, FamilySearch.

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara O Te Kawanatanga; Land Records.

Catholic Diocese of Dunedin, St Mary’s Church, Milton; Baptism Register.

Fairfax Cemetery Records, Dunedin Public Library.

Godziszewo, Miłobądz & Tczew Parish Records, Pelplin Diocese, Poland.

Antonio Anicich and Ellen (nee Plewa), Block 17 Plots 280 & 281 at Fairfax Cemetery near Milton

Hannagan Daphne, Dunedin, supplied family articles & documents.

Jensen John, Mosgiel, Plewa family history and John’s life story (2022)

New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs Naturalisations, Births, Deaths and Marriages.

New Zealand Government Property Tax Department, from the rates assessment rolls, Return of Freeholders of New Zealand 1882, published 1884.

Websites

Fairfax Cemetery – August Plever (1847-1923) – Find a Grave Memorial

Fairfax Cemetery – Ellen Anicich (1871-1941) – Find a Grave Memorial

Fairfax Cemetery – Frances Plever (1839-1934) – Find a Grave Memorial

Fairfax Cemetery – Francis Plever (1869-1916) – Find a Grave Memorial

Compiled by Paul Klemick (2022)

Chairperson ..... Ewa Rożecka Pollard

Phone ......+64 3 477 5552

Secretary ..... Anna McCreath Munro

Phone ..... +64 3 464 0053

Facebook ..... Poles Down South

Contact Poles Down South

Poles in New Zealand We would like to hear from Poles or people with any Polish connection, who visited New Zealand and particularly those of you who paid a visit or lived anywhere in Otago or Southland.

....................

Polski “Poles Down South” jest stroną internetową organizacji polonijnej w Nowej Zelandii działającej w rejonie Otago i Southland na Wyspie Południowej. Siedzibą organizacji jest Dunedin.